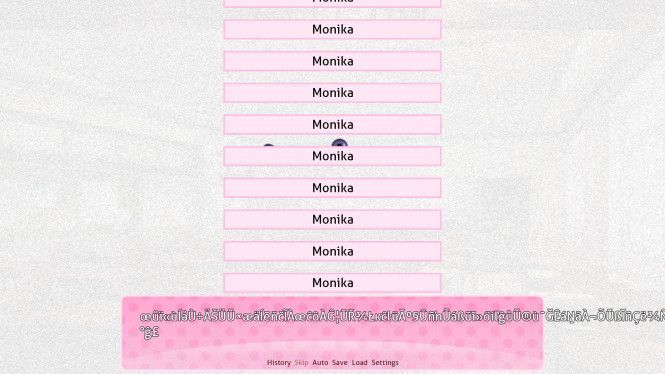

Ha-ha, what a stupid dog. Too stubborn to admit that it was wrong, so it wasted all of its energy digging. Ha-ha, funny dumb animals. Look at the top of the comic, though. “Sunk Cost Effect.” That might ring a bell, at least for you behavioral economics junkies. Put succinctly, the sunk cost effect is the tendency for people to continue pursuing some endeavor because they have already invested (“sunk”) a lot of time and effort into it, even if that endeavor is no longer the best option available to them.

Intuitively, it makes sense. We humans like seeing the results of our labors, and we don’t like to just up and discard them. But sometimes, that’s the correct option. The efforts or money we’ve expended are “sunk.” Unrecoupable. We can’t get them back. We can’t un-spend that effort or those dollars. So we should look only to the present and the future, no matter how wasteful of a decision the initial effort was.

“Ugh,” you say, rolling your eyes. “That’s fine, but who cares? I’m not a behavioral economist, and neither are you. You’re just a stuck-up person who likes pretending to be smart by talking about intellectual things like this.”

True, perhaps. But that doesn’t mean what I have to say isn’t relevant. Mosey on over to the other side of the Atlantic, and have a look at our friends in the United Kingdom. The U.K. is currently embroiled in a debate over the infamous issue of “Brexit,” or a British exit from the European Union. The referendum approving Brexit took nearly three years ago. And yet Britain is still paralyzed, caught in a parliamentary deadlock. Reformists call for a second vote on the issue, while hardliners demand an immediate exit – or “no-deal Brexit.” I’d like to focus on this last group, and in particular an argument I often hear in favor of their position.

“We’ve spent 66 billion pounds on Brexit already. We’ve spent so much. We can’t turn back now.”

A classic sunk cost. I don’t seek to support or condemn the no-deal Brexit position. There are legitimate arguments to be made in favor of it, even if I may not personally agree with them. But the “we’ve already spent so much” argument is definitively not legitimate. Those 66 billion pounds are spent, and they can’t be un-spent. You know what “we’ve already spent so much” really means? It means, “we’ve already spent so much, and we’ll look stupid if we change our minds now.” Well, yes. It would look stupid. But if changing course is the best thing to do, then so be it. It’s okay to look stupid, if it’s the right thing to do.

However, I don’t mean to pick solely on our friends across the pond. We are guilty, perhaps more so, in our own political discourse. Recall the 2012 election cycle. (Feels like an eternity ago, doesn’t it?)

(Those are real flip-flops, by the way. You can buy them from some obscure corner of the Internet.)

Critics of all ideological flavors lambasted Mitt Romney for his “flip-flopping,” deciding that disqualified him as a capable leader. While I recognize the need for leaders to be consistent, we simply go too far. Shockingly, it is possible for people to take a viewpoint, learn new information that affects their views, and change their point of view. This is healthy, and in fact necessary in order to have well-informed and flexible leaders. Obviously, we shouldn’t support politicians flipping stances left and right. But when they have a genuine, informed change of heart, we should applaud that. They shouldn’t be afraid of looking weak just because they changed their mind for a valid reason.

One last thing. Do me a favor, reader, and watch the video I’ve attached below.

That’s Marie Kondo, creator of the famous KonMari method for tidying up and self-described “organizing consultant.” Is she out of place in this piece about sunk costs and behavioral economics? Not at all. In fact, I would argue she is one of the greatest behavioral economists of the modern era.

Let me tell you one more story. Suppose you’re just an ordinary consumer. On a whim, you bought yourself some useless kitchen tool that sits in your drawers, collecting dust. It sits there, useless, but out of sight. Now suppose you have another kitchen tool. Throw in a few papers or documents that you keep just because they might be important someday. Newspapers, magazines. Paper clips. Plastic bags. You keep it all because there might be some use for them in the far future. It piles up. You can’t open the drawer or look at your desk without feeling stressed. It’s terrible. But you have to keep it. Selling those objections or giving them away or even throwing them away would be an admission of defeat, an admission that it was a bad idea to acquire the objects in question in the first place. Right?

Wrong, says Marie Kondo. True, the purchase might have been stupid in the first place. But, once again: the money you spent on those things is spent, and it can’t be unspent. It doesn’t matter what happened then, when you bought them. What matters is now. Do those things spark joy? Fine, keep them. Do they not spark joy? Does keeping them around just contribute to the clutter and stress them out? That’s fine too. Acknowledge that they were a bad purchase, and move on.

No, really! It’s okay to be wrong. It’s okay. Normal. Healthy. What matters is that you recognize your wrongness, and that you let go of your attachment to it. Don’t continue to cling on to that wrongness, digging yourself deeper and deeper, just because it’s been a part of your life for so long. Let it go, look forward, and do what’s right. And that goes for everyone. Go ahead and eBay your three avocado slicers, recycle your stack of magazines, donate those clothes that look bad on you and clog up your closet. It’s okay to be wrong. Just don’t be wrong for long.

P.S.: Just for fun, another one of those comics. It’s called “Behavioral Economics for Dogs,” written by some folks at Duke University. Check them out!